Welcome!

Welcome to our 2022 production of From the Mississippi Delta by Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland. It is our hope that this study guide enhances your experience before, during, and after you watch the show.

If other questions arise that are not answered in the guide, please feel free to reach out to us. We are here to make sure you have an enriching and positive experience at our theater, whether it is virtual or in-person. Reach out to our Director of Education, Jenny Nelson, at jnelson@westportplayhouse.org and she’ll be happy to answer your questions.

more on the show

WHAT WE BELIEVE

Land Acknowledgement

Westport Country Playhouse acknowledges the indigenous peoples and nations of the Paugussett that stewarded the land and waterways of Westport, Connecticut. We honor and respect the enduring relationship that exists between these peoples and nations and this land.

Antiracism statement of purpose

We resolve to place antiracism at the center of our work. We are committed to holding ourselves accountable to short-and long-term goals, while realizing that this work has no endpoint and will evolve and change. We realize and acknowledge that this is an educational process for which we ourselves are responsible.

Synopsis

The journey begins in Greenwood, Mississippi — the Delta. “In my Delta town, some Black girls aspired to become the woman — the mistress of some wealthy white man. But the darker ones — like me — could make it by going to the cotton fields, working from sun to sun, for just about three dollars a day,” laments Phelia (Holland’s alter-ego). It is those and other dreadful experiences that inspire her to dream far beyond the funny-paper walls in her drafty shotgun house in Dixie Lane Alley. Phelia’s mother, Aint Baby, is a powerful influence. A midwife who delivers babies of poor black and white women, she also rents out rooms to prostitutes, as a way “t’ make a livin’ for me an’ my chulluns.” On her 11th birthday, Phelia’s childhood is brutally stolen from her by a white man and soon after, Phelia plots a series of escapes. After the assault, she attempts to join a minstrel show as a dancer, astounding the audience, but the plan is quickly thwarted. At the age of 12, Phelia is forced to become a sex worker. At 14, she quit school, was briefly incarcerated, and by 16, she was a single mother.

Then the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) comes to town, and Phelia is swept into the momentum of the civil rights movement. Tragically, Aint Baby is killed when her house is firebombed, and a heartbroken, but determined Phelia goes off to meet her destiny in the North. There she finds herself lured into the alluring world of sex workers. Amazingly, she is encouraged and supported by a community of civil rights workers, friends and her fellow sex workers to attend college.

The journey ends, 20 years later, as Phelia literally dances across the stage at the University of Minnesota to accept her Ph.D. Inspired by Alice Walker’s poem “Revolutionary Petunias,” the play closes with an emotional tribute to unsung Black heroes — extraordinary, ordinary women who are the backbone of the Black community.

About the Playwright

When Ida Mae Holland entered the world on August 29, 1944, in Greenwood, Mississippi, no one could have predicted the odyssey that would become her life. “Cat,” as she was nicknamed, was born in a rundown, drafty shotgun house to a poor but strong black woman, who already had three children, no formal education, and limited employment choices. Curious, smart and precocious, young Ida learned from her mother, Ida Mae — familiarly known as Aint Baby — how to dream big dreams, for herself and others, in their impoverished Delta community. During the 1940s and 1950s, Greenwood was a place where black people lived in fear of their lives — and rightfully so, as lynchings, sexual assaults, firebombings and a range of unimaginably gruesome atrocities were commonplace.

When Ida Mae Holland entered the world on August 29, 1944, in Greenwood, Mississippi, no one could have predicted the odyssey that would become her life. “Cat,” as she was nicknamed, was born in a rundown, drafty shotgun house to a poor but strong black woman, who already had three children, no formal education, and limited employment choices. Curious, smart and precocious, young Ida learned from her mother, Ida Mae — familiarly known as Aint Baby — how to dream big dreams, for herself and others, in their impoverished Delta community. During the 1940s and 1950s, Greenwood was a place where black people lived in fear of their lives — and rightfully so, as lynchings, sexual assaults, firebombings and a range of unimaginably gruesome atrocities were commonplace.

Sexual assaulted by a white man on her 11th birthday, expelled from school, a sex worker at 12 and a mother at 15, Holland was headed in the wrong direction; that is, until the civil rights movement came to her town. She was swept into the momentum, participating in sit-ins, mass rallies, even going to jail with other activists, and her life was transformed. “From that moment on I said I could be somebody,” she writes in her memoir. In retaliation for her daughter’s activism, Aint Baby’s home was firebombed by members of the Klan and she was killed. Devastated but determined, Holland earned her GED, and in 1966 she moved north to Minneapolis. Soon afterward, she added “Endesha” to her name — Swahili for “one who drives herself and others forward.” Subsequently, Holland earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees as well as a doctorate from the University of Minnesota in American studies, with a concentration in theatre arts (playwriting). The first of her plays, The Second Doctor Lady, is about her mother, whose skill and competency earned her the title, and it won the Lorraine Hansberry Award for Best Play in 1981. From the Mississippi Delta, her sixth play and part of a trilogy, has earned critical acclaim and has been nationally and internationally celebrated as an inspiring dramatic portrayal of the human experience, as viewed through the eyes of a Black woman. (Holland’s memoir, also entitled From the Mississippi Delta, was originally published by Simon & Schuster and is available in hardcover and paperback in bookstores.)

Dr. Endesha, as she was called by her students, was a professor emerita from the University of Southern California, where she held joint appointments both in the School of Theatre and the program of the Study of Women and Men in Society (SWMS) from 1993 to 2003. Forced into early retirement and a wheelchair by ataxia, a hereditary, neuromuscular disorder, Holland passed away in 2006. Her legacy to her students and audiences around the world is one of determination, hope, motivation and inspiration. She holds herself up to the light as a constant reminder that anyone can make it, anyone can survive… anyone can be somebody.

— Dr. Habibi Minnie Wilson, Los Angeles, Calif., 2005

.

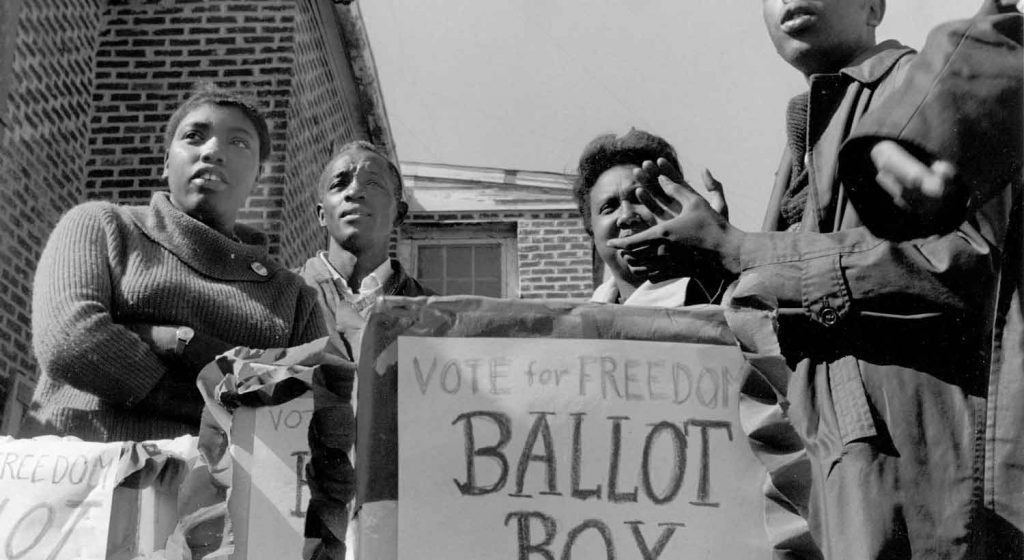

Spotlight on The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ‘Snik’) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ‘Snik’) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s.

Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, the Committee sought to coordinate and assist direct-action challenges to the civic segregation and political exclusion of African Americans.

From 1962, with the support of the Voter Education Project, SNCC committed to the registration and mobilization of black voters in the Deep South. Affiliates such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama also worked to increase the pressure on the federal and state government to enforce constitutional protections.

By the mid-1960s the measured nature of the gains made, and the violence with which they were resisted, were generating dissent from the group’s principles of nonviolence, of white participation in the movement, and of field-driven, as opposed to national-office, leadership and direction. At the same time some original organizers were now working with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and others were being lost to a de-segregating Democratic Party and to federally-funded anti-poverty programs. Following an aborted merger with the Black Panther Party in 1968, SNCC effectively dissolved.

Because of the successes of its early years, SNCC is credited with breaking down barriers, both institutional and psychological, to the empowerment of African-American communities.

.

Interview with director Goldie E. Patrick

Goldie E. Patrick spoke with our Director of Education Jenny Nelson about our upcoming production of From the Mississippi Delta.

Jenny Nelson: Why do you think the Playhouse selected this play?

Goldie E. Patrick: I thought it was an interesting choice for the play to be presented in Westport considering the community and the town’s demographic. So I was intrigued. When I found out that Dr. Holland wanted the play to be produced more, I was excited to respond to that charge. A lot of the time, Black theater is restricted to maybe 7 or 10 Black playwrights [in our country]. I wasn’t familiar with this play. I asked myself, “Why don’t I know this play?” and then I was like, well, there’ll be a lot of people that don’t know this play.” So this is an opportunity to highlight Dr. Holland’s voice and her contribution to society — and also to American theater.

I also realized that my decision was spiritually charged. I am the third generation to carry the name Goldie. I think about Dr. Holland being named for her mother. The middle name “Mae” indicates you are named after the woman before you. So, that’s how you differentiate between Ida Mae (the daughter) and Ida (the mother). So, I also have a real connection to telling the story of those of us that walk with the women before us that are named for the women before us. So now I feel like the play chose me to talk about how you can heal generational trauma by seeking your own freedom, and so that’s why I think I’m here to direct this. That’s gonna be my chart. I love the change of perspective and narrative in the stories of these women. None of these women are victims. They’re survivors. That’s huge. It’s a significant perspective that I want to bring to this story, the story of survivors’ perseverance.

JN: A director’s concept typically centers around the director’s point of view of the story and/or overall vision for the production. What is your concept for this production?

GEP: The concept for this production is about the seeds that we plant. There is a proverb that is really big on social media right now that says, “They thought that they could bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.” Conceptually, I’m looking at what is planted. There are plenty of things that are planted that aren’t nourished to grow, and so they don’t grow. There are things that are planted, and they grow, and they blossom, and then you pick them, and so that’s the end of their experience. But what happens when something gets planted, and it grows? It grows no matter where it is, and it grows, and it blooms, and then it grows and blooms and has seedlings. Conceptually, I’m looking at planting, intentional planting, intentional nurturing, pruning in the process, but also replanting if it gets uprooted.

I’m also exploring the tradition of innovation for survival. I think this idea is aligned directly with the Black American experience. A lot of times, historically, we don’t talk about the Reconstruction period in American history, but it’s such a significant period, because if we skip the emancipation of enslaved Africans, if we skip Reconstruction, we skip the part where we were fine. We skip the part where we survived, where we flourished, right? We go instantly into Jim Crow. So this play, there are elements where I’m really exploring the ways that we built with what we have.

And then the last one is a reclamation of Black girlhood, which is kind of just my thing. That’s the thing I always lean into — the ways we grow ourselves up, the way we support throwing each other up. We do it in our little secret passageways that we identify with each other.

JN: Were there any particular current events, books, music, etc. that inspired your concept?

GEP: Dr. Holland references Alice Walker’s book of poetry, Revoutionary Petunias. I am a huge Alice Walker fan. My identity as a womanist is because of Alice Walker, and I think Alice Walker is a profound scholar of Black women’s identity politically and artistically and socially, in both her work and her examples. So I was very inspired by that to lean into Black folx’ everyday acts that are normal as really bold or radical when you think about what it is. That was definitely inspiring, and I think that’s the kind of tone that I see for the characters in the play.

I listened to a lot of Delta Blues. I listened to a lot of Nina Simone. Right now I’m listening to Four Women by Nina Simone. Particularly because Nina has popularity in the North and is sometimes detached from her identity from the South. So she brings her southern consciousness but her sound is so classically trained and gained prominence in America. So it’s a combination of both the North and the South.

Mississippi itself is a huge inspiration for this. I love it. I love the downtown. I love the air, the geography. The dirt is different down there. I love the red clay dirt of the South. I love the people, and right now Jackson, Mississippi is suffering from a water crisis. Let me tell you a story. Chokwe Lumumba Jr. is the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi. He had a significant victory when he became mayor. He’s 39 years old. He is the son of Chokwe Lumumba, who was the political activist who was tied to so many black liberation movements. He was considered a threat to America, but he became a political leader. He was a defense attorney for political prisoners for the Black Panther movement and those civil rights movements.

So Jackson, Mississippi and [the political leaders] are so significant because we’re looking at the generational story of political leadership in that city right now. The politics in Jackson are so significant to what’s happening in terms of the environmental injustice of what’s happening, they’re not separate. So that’s been very much on my radar as I think about the voices of Mississippi.

JN: How does sound design play a role in supporting your concept?

GEP: As a director, the design elements are very much a part of my process. Michael Keck, my sound designer, is brilliant. He’s brilliant. I love our collaboration, because my mantra is “I can’t wait to say yes.” So it’s been a learning opportunity for me to not make any musical decisions, and instead say “yes” to our designers. The sound for this production is far beyond like a song or lyric. It is very, it’s very, in the gut, it’s very visceral. He is exploring that sound that is beyond popular music. The music is designed to mirror how Dr. Holland has written the sounds of the South in her play, the people, nature. It’s not necessarily just the popular music that we equate to the south.

JN: Is there anything you’d like to add that might enhance the audience’s experience?

GEP: I hope that they see themselves in the perseverance of Dr. Holland, her unapologetic quest for freedom and opportunity. I hope this production inspires them to want to know more about the South. They want to know more about the time period and everyday life for Black folx during that time. I hope that they imagine the world radically and beyond what they have experienced. Because that’s what Dr. Holland was trying to do. She was down to change what didn’t work for her, even if that meant she had to leave what she knew. I hope they also think about where they want to travel because you don’t have to do the work at home the whole time. You can leave home and come back with the knowledge for folx. It’s a journey.

Before you see the show

Listen and Explore

The playwright utilizes music throughout play to create a sense of time, place and mood. Let’s listen to some of the songs from the play to gain a deeper understanding of the story. Try listening to each song on its own, and listen to the tempo and energy of the music.

Here are some a questions to ask yourself as you listen:

- What genre or type of music is it?

- Is the tempo fast or slow?

- How do the lyrics of the song support the story?

- How does the music make you feel when you listen to it?

Listen to “Trouble in Mind”

Lyrics and music written by Richard M. Jones. Recorded by Sister Rosetta Tharpe in 1941.

Listen to “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”

A traditional spiritual that dates back to the period of enslavement in the United States. Recorded by Odetta live at Carnegie Hall in 1960.

Listen to “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around”

A freedom song based on the spiritual “Don’t You Let Nobody Turn You Round” that became an American civil rights-era anthem. It was often sung during civil rights demonstrations in the United States. Recorded by Sweet Honey in the Rock.

Listen to “Oh Freedom/Come Go and With Me/I’m on My Way”

A post-Civil War, African American freedom song. It is often associated with the civil rights movement, with Odetta, who recorded it as part of the “Spiritual Trilogy,” on her 1963 album Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues, and with Joan Baez, who performed the song at the 1963 March on Washington. Recorded by Odetta in 1963.

Listen to “We Shall Overcome”

A gospel song which became a protest song and a key anthem of the American civil rights movement. The song is most commonly attributed as being lyrically descended from “I’ll Overcome Some Day”, a hymn by Charles Albert Tindley that was first published in 1901. Recorded by The Boys Choir of Harlem in 2001.

Listen to “This Little Light of Mine”

A popular gospel song of unknown origin. Adapted in the 1920s by Harry Dixon Loes. Recorded by Gospel Dream in 2009.

Listen to “Will the Circle be Unbroken”

A popular Christian hymn written in 1907 by Ada R. Habershon with music by Charles H. Gabriel. Recorded by John Lee Hooker in 1973.

Listen to “My Home is in the Delta”

Written and recorded by Muddy Waters in 1964.

AFTER YOU SEE THE SHOW

Investigate the following THEMES

Travel

Resiliency

Ancestors

Storytelling

Midwifery

Investigate the following SYMBOLS

North Star

The Water Meter

Seeds

The Delta

EXTENSION ACTIVITIES

Activity: “I’m from a place...”

One of the recurring themes in our production of From the Mississippi Delta is the concept of home.

- As a class, discuss the reasons why Ida Mae and Ain’t Baby leave their homes.

- Discuss why a person might leave their home and live in a new place.

- Discuss some of the reasons a person of color might leave their home during the different time periods of our story: 1940s, 1960s and 1980s.

Dig deeper

Journal about your home — your country, state, town, or even dwelling (house, apartment, manufactured home, etc.) — and how you feel about your home. What is the significance of your home?

If you want to dig even deeper

Try journaling about your parent(s), grandparent(s) or significant loved one(s)’ home. If you don’t know about their home, it might be an interesting thought exercise to ask them about it. Start a conversation. You never know what you may learn about your ancestors and your heritage.

Learn more about family structures

One of the recurring motifs in the play is the examination of one’s given family and one’s chosen family. To learn more about familial structures, we’d like for you to visit the PBS project, “The Storytelling Portrait.” This project asked people all over the country to submit their individual stories by responding to one of a number of thought-provoking prompts. Whether joy or sorrow, triumph or hardship, family traditions followed for decades or just the morning school run, this is a picture of life as it is really lived. American Portrait gives us a glimpse into the lives of people across the country and helps their stories be heard. Watch now: PBS American Portrait »

.

Activity: My Family Tree

Now that you’ve explored different types of family structures, we’d like for you to investigate your own family.

- To begin, decide whether you’d like to explore your given or chosen family or both.

- Pick a family member to interview. This person should be someone you feel comfortable with and will be open to answering questions about themselves and your family.

- Let’s think of some questions you could ask to gain a deeper understanding of your family members.

Below are a couple examples to get you started. Can you think of more?

- Where were you born? (country, state, town/city, hospital/home/other)

- Do you know your birth story?

- What are your parent(s) names? Do you know their birth story?

- Can you recall a funny memory about our family? A sad one?

- Are there any special heirlooms from our family that you treasure? If not, could we purchase/create one together?

- What does legacy mean to you? What do you hope your legacy will be?

FURTHER READING & RESOURCES

Book List

Revolutionary Petunias and other Poems

by Alice Walker

Delivered by Midwives: African American Midwifery in the Twentieth-Century South

by Jenny M. Luke

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration

by Isabel Wilkerson

Make Good the Promises: Reclaiming Reconstruction and Its Legacies

By Kinshasha Holman Conwill and Paul Gardullo

VIDEO

The Great Migration: Crash Course Black American History

Nina Simone: To Be Young, Gifted and Black

Interview with Alice Walker from the program “Poems for the Listener” (1984)

More questions?

Reach out to our Director of Education, Jenny Nelson, at jnelson@westportplayhouse.org and she’ll be happy to answer your questions.

We hope you enjoy the show!